It’s not common practice to present a film at a book festival, but e.E. Charlton-Trujillo is not a common artist. For starters, her name is a nod to her adoptive family, her birth mother, and e.e. cummings.

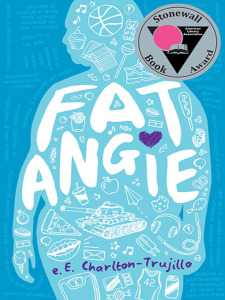

The native of the small South Texas town of Mathis is all over the map, literally and figuratively. A Renaissance woman of the arts—award-winning filmmaker, playwright, novelist, poet—Charlton-Trujillo’s third novel spawned a cross-country tour that resulted in the formation of a nonprofit. In the young adult novel Fat Angie, a high school freshman endures the disappearance of her sister in Iraq, weight issues, and the possibility of being gay, and the resulting bullying exacerbated by a heartless mother and turncoat brother. The novel was chosen for the American Library Association’s Stonewall Award 2014 for exceptional merit relating to the gay/lesbian/bisexual/transgender experience and was a Lambda Literary Finalist.

The documentary that resulted out of the cross-country drive sharing her love of writing with young people, At-Risk Summer Movie, will screen at the Texas Book Festival on Sunday at 3 p.m. at in Capitol Auditorium Room E1.004.

e.E. Charlton-Trujillo

You’re coming back to the Texas Book Festival to present At-Risk Summer Movie, which grew out of Fat Angie. How did that documentary come about?

I met a kid in a tiny South Texas town in May of 2013. Super creative kid but very depressive, struggling to fit socially. His teacher showed me a piece he did and asked if I would meet him. We sat down, and I started talking about this thing he wrote, and the kid who doesn’t look up from the desk is looking up, and he’s looking at me, and the kid who doesn’t talk is now talking to me, and the kid who doesn’t smile is now smiling. We talked about writing. We talked about some of the themes that were in Fat Angie.

But it wasn’t a book talk, it was a talk talk—a creativity talk. And I got this wild idea: What if I tried to do this with a lot of kids? Can I do this? Will it matter? That crazy idea took flight. I gave up my comfortable loft, closed my business, put everything in storage, rented a Ford Focus, and drove across America working with at-risk youth at no cost to their programs. What is “at-risk”? Is it the kid in Texas who doesn’t have the access to creative mentorship? Is it the rich kid whose parents aren’t engaged? Is it the inner-city kid who’s African-American and struggling to get food on the table? Is it the gay kid? We want to remove the fear of that term. These are kids. Let’s just give them a shot at being better. Just give them a chance.

And it’s important to note that I have a fear of being in cars.

So how would you describe the film that came out of the experience?

It’s not a film about just one thing, and that’s either going to be a blessing or a curse. It’s part road movie, part my journey, part the journey of the young people and their writing, and it’s the journey of educators and librarians and independent booksellers. You have all of these people who are part of this larger story.

You’ve said that the kids you met changed your life. How so?

These kids are the clearance kids, the throwaway kids. They’ve been in gangs or are teen moms or have punk rock hair or their hair is too long. Take your pick. They teach you who you are and how showing up has currency with them. If you try to be someone other than yourself, they call you on it. I’m a better and more evolved person because I allowed myself to be present and do the work with them, to have fun, to listen to their stories. That was the most valuable thing. They got a chance to be heard, and so often they do not feel that is a viable opportunity.

Photos provided by e.E. Charlton-Trujillo

What are the reverberations from the kids you visited last summer?

I’m so proud of one kid. He was part of what became known as the Fair View Six (named for an alternative high school in Chico, California). I asked, “Has anyone thought about suicide?” All six hands go up. And I asked, “Has anyone attempted suicide?” and five hands go up, which was just chilling, because they weren’t picked for that reason. One of them recently did slam poetry about his attempted suicide. Here is a kid whose family members have committed suicide, who has been bullied, who was pushed to the edge, and he’s standing up and he’s telling his story.

You’re in the process of creating a nonprofit called Never Counted Out. Where does that fit into the picture?

The book created the tour. The tour created the movie, and now those three have created Never Counted Out. The primary function at this point is to get artists and youth in the same space. Say you’re a sculptor. You’d go to an at-risk program to engage with them in discussion and sculpting. You’re not just doing a workshop on sculpting. You’re teaching them something about themselves. We only ask for them to do it one hour a year, but our little mighty group believes that one hour could turn the tide for a kid. It’s like a little spark that offers them a chance to think of something in a way they haven’t thought of it before, and to see that someone actually cares. A secondary function is collecting donated books from famous authors and people who have collected books by the truckloads. We’ll mail those to at-risk programs all over the country.

‘Fat Angie’

Where did Fat Angie come from?

This is going to sound crazy, but I was sitting in a mom and pop diner in Madison, Wisconsin, deep in the winter. I turned on my old school iPod and landed on a Lenny Kravitz song called Are You Gonna Go My Way? There was something in that sound in the dead of winter that basically gave me the whole first chapter of the book. I grabbed a pen from a waitress named Grace and wrote the opening chapter on a series of napkins. I always think of Fat Angie as something that found me.

There are so many different themes. Issues of bullying, of belonging, of family, of sexuality, of war, of community. For some people, that’s way too many, and for some, well, that’s how life is. You don’t just live one or two storylines at a time.

What led you to begin writing novels in the first place?

Prizefighter en Mi Casa, which is set in South Texas, is my first novel. My best friend had been killed in a car accident. I was struggling a good deal around that. I wound up being homeless—here I was with an MFA and not able to get my life together. Basically I got dared to write it. So in this moment of absolute raw, stripped-down pain and dealing with the loss of my friend, I was able to take writing and channel my darkest moments into it. It was about making creativity the most powerful thing to deal with that grief as opposed to being self-destructive or running away from life. That book made me face life again, because I didn’t know how to be. By writing—by being a part of those characters and their world—made me also want to be a part of this world again. That’s why I think writing is a really power tool that I encourage young people to embrace. [Her second was Feels Like Home.] And then Fat Angie just showed me I didn’t need to be in the dark to write.

How do you feel about coming back to Texas for the festival? [She now makes her home in Cleveland, Ohio.]

Regardless of where I live, Texas is my home. There is something kind of magical about coming back to my home state with this film and say, “I learned about diversity and how to be a good person in this state, and now I get to bring this back to you. This is what I’ve done as a person.”

Interview by Jana Hunter.